Bob Dylan’s performance at the Newport (Rhode Island) Folk Festival in 1965 is widely regarded as one of the pivotal moments in the history of rock music. But if there is near consensus on its importance, there is much less agreement on exactly what happened. Rock historians, Dylan’s biographers, and eyewitnesses provide varying accounts of the audience’s reaction to Dylan’s performance, the reasons behind those reactions, and Dylan’s response.

This much is clear: when Dylan took the stage at Newport on July 25, 1965, he was the leading light of the folk music revival of the early 1960s. Based on traditional American musical forms and steeped in the populist politics of the 1930s, the revival was meshed with the ongoing civil rights movement and thrived on topical songwriting. The pursuit of “authenticity” lay at the heart of the revival, and as such it was generally believed that real folk music was played only on acoustic instruments. Folk purists had little respect for rock and roll, which most regarded as puerile and crassly commercial.

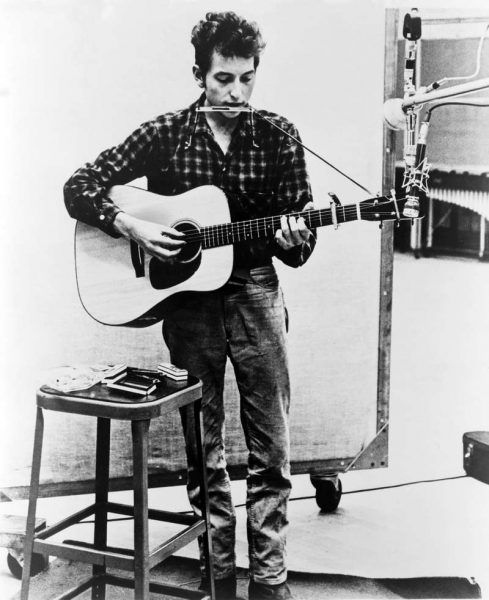

In the months leading up to Newport, Dylan, theretofore the quintessential acoustic troubadour, had released the partly electric album Bringing It All Back Home and had recorded much of Highway 61 Revisited with rock-oriented musicians and electric instruments. The week of the 1965 festival, Dylan’s acerbic single “Like a Rolling Stone” was omnipresent on U.S. Top 40 radio. Called electric blues by some and rock and roll by others, it was unquestionably not the folk music for which he was known.

Interested in duplicating this electric sound live, Dylan hastily recruited members of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, along with session pianist Barry Goldberg and keyboardist Al Kooper, who had created the signature organ sound on “Rolling Stone,” to act as the backing band for his set at Newport. Brandishing a solid-body electric guitar, Dylan “plugged in” with the rest of the band. The set began with “Maggie’s Farm” from Highway 61. This is where the accounts diverge. Some (notably critic and biographer Robert Shelton) reported that the audience immediately “registered hostility” and that boos and catcalls (“Play folk music!” “Get rid of the band!”) began at the end of “Maggie’s Farm” and escalated through the next song, “Like a Rolling Stone.” Dylan biographer Anthony Scaduto described the audience’s initial reaction as a mixture of scattered booing and applause but mostly bewildered silence. According to Scaduto, booing and heckling then spread throughout the audience during “Rolling Stone,” driving Dylan and the band offstage after the performance of a third song, an early version of “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.”

Scaduto cited an interpretation of the event by folk musician Eric (”Ric”) von Schmidt that has been echoed by others (notably biographer Bob Spitz, who also reported that some audience members booed as soon as they realized that amplified instruments were going to be used). According to von Schmidt, Dylan’s voice was overwhelmed by the band as the result of poor sound mix (which most accounts describe as muddy or unbalanced at best), leading the people closest to the stage to call out that they couldn’t make out Dylan’s words (“Can’t hear ya!” “Turn the sound down!”). The members of the audience who were farther back, said von Schmidt, misunderstood the complaints and responded with booing and jeering—probably based on the belief that Dylan was betraying folk music by going electric. What is certain is that there was booing (and cheering) and that after three songs Dylan and the band left the stage. According to Kooper, who was at Dylan’s side onstage, the performers left because they had rehearsed only three songs, and the booing was primarily a response to the brevity of the set by the performer whom most of the audience had come to hear.

There also are varying accounts of what transpired backstage during the performance, but it seems likely that a confrontation took place at the sound board between festival board members: folklorist Alan Lomax and eminent folksinger Pete Seeger wanted to cut the electricity; Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman, and Peter Yarrow (of Peter, Paul and Mary) successfully opposed them. Dylan returned to the stage with an acoustic guitar (at Yarrow’s behest, according to most accounts) and was greeted by thunderous applause. He performed “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “It’s All Over Now Baby Blue,” and as he did so, according to Greil Marcus in Invisible Republic, there were tears in Dylan’s eyes. Scaduto too described the tears, and several accounts characterize Dylan as shaken and confused. Kooper, on the other hand, said there were no tears.

And so the debate lives on, decades after the event. But what no one denies is that folk and rock music were never the same after that memorable day at Newport in 1965.

Jeff Wallenfeldt